What a 1980s Facial-Scar Experiment Shows About How We See Discrimination

In 1980, at Dartmouth College, psychologists Richard E. Kleck and Angelo G. Strenta set out to study how people perceive subtle social cues. In their own mischievous words, “Individuals were led to believe that they were perceived as physically deviant in the eyes of an interactant.”

Over a series of studies, dozens of volunteers (mostly females) pretended to have a physical ailment or disfigurement — often a facial scar — during an interview. The rub was this: the person pretending to have the disfigurement was the true test subject.

To make volunteers believe they bore a scar, each subject sat down with a professional makeup artist, who carefully applied a facial “injury.” The participants were shown their fake scar in a hand mirror and given a moment to absorb their appearance. But before meeting the stranger, the makeup artist returned under the pretense of “touching up” the scar — and quietly removed it. Participants were unaware of the subterfuge and entered their interview convinced their face still bore the disfigurement.

Even though no scar was present, nearly all subjects reported that the strangers they met seemed uneasy by their appearance — avoiding eye contact, speaking awkwardly, or looking at them with pity.

A Distorted ‘Social Reality’

What Kleck and Strenta had uncovered was how easily human expectations about how we’re perceived can color — and distort — our reading of other people’s behavior.

Though the study was groundbreaking, previous studies had treaded similar ground. This included Beatrice A. Wright’s “Physical Disability: A Psychological Approach,” which had found that once a person acquires a physical disability, their perception of social reality becomes filtered through that disability.

While Kleck and Strenta noted that their research differed from Wright’s in key ways, they also saw a clear connection, noting “that persons who are permanently physically deviant make the same kinds of disability-linked attributes to a natural stream of behavior as did the subjects in the present studies.”

The findings of Kleck and Strenta are highly relevant half a century later. In modern America, it’s not uncommon for people to see their group identity as a kind of social handicap. The idea that certain identity groups face discrimination has taken root in the American mind. For example, a May 2025 Pew Research survey asked Americans how much discrimination they think various groups face. Their responses are instructive:

- Illegal Immigrants: 82% say some (57% say “a lot”)

- Transgender people: 77%

- Muslims: 74%

- Jews: 72%

- Black people: 74%

- Hispanic people: 72%

- Asian people: 66%

- Legal immigrants: 65%

- Gay/Lesbian individuals: 70%

- Women: 64%

- Older people: 59%

- Religious people: 57%

Discrimination certainly exists, at both the individual and collective level. No doubt some individuals in all these groups have faced discrimination, just as some individuals have in groups less commonly associated with it, such as rural Americans (41%), young people (40%), white people (38%), and atheists (33%).

Kleck and Strenta’s experiment shows that people often believe they’re being discriminated against because they expect to be, not because they are. Edgier comedies of the 1990s explored this idea.

In one Seinfeld episode, Jerry is on a date and stops to ask a mailman (whose face is obscured) if he knows where a certain Chinese restaurant is. “Excuse me, you must know where the Chinese restaurant is around here,” the comedian says.

Things get awkward, however, when it turns out the mailman is Asian. “Why must I know? Because I’m Chinese?” the mailman says in a heavy accent. “You think I know where all the Chinese restaurants are?”

The scene is comical and a bit absurd, but it reflects a phenomenon Kleck and Strenta observed in their experiments: Once humans begin to feel they are being treated differently based on their physical appearance or inherent attributes, they will believe people are treating them differently even when that is not the case.

“… if we expect others to react negatively to some aspect of our physical appearance,” the authors wrote, “there is probably little those others can do to prevent us from confirming our expectation.”

The Cost of Victimhood Culture

I learned about the Kleck-Strenta as an undergraduate in an introductory psychology class nearly 30 years ago. But I had rarely thought about it since — until Konstantin Kisin, a British-Russian political commentator, brought it up in recent podcast appearances and connected the study to the rise of victimhood culture.

“If you preach to people constantly that we’re all oppressed, that we’re all being discriminated against, then that primes people to look for that,” says Kisin, “even where it doesn’t exist.”

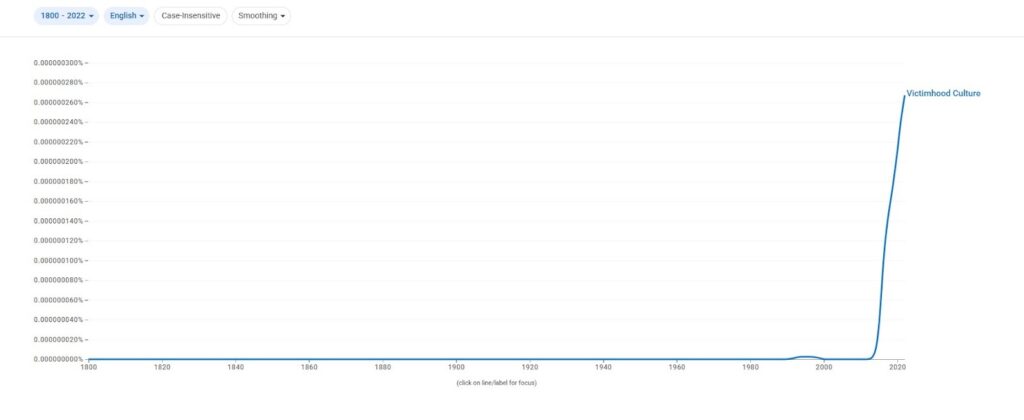

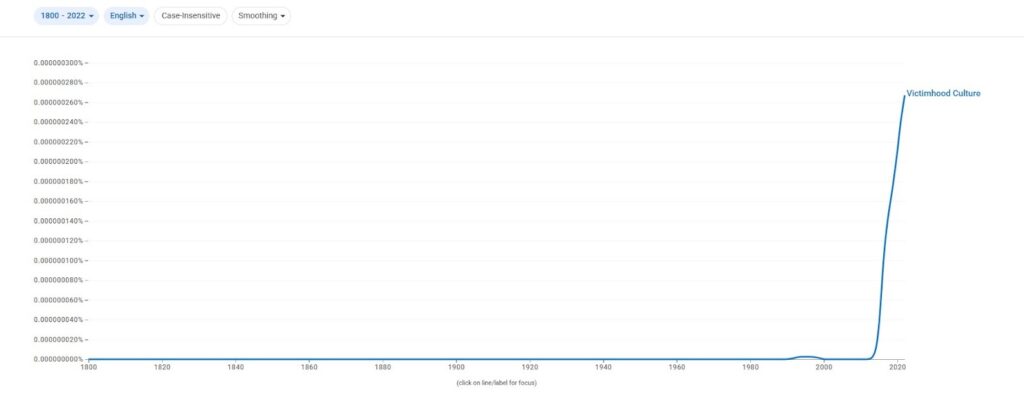

As a concept, victimhood culture wasn’t articulated until the 1990s. But by 2015, the phenomenon was widely discussed in academic literature and mainstream publications, likely due to the rise of political correctness that preceded it.

“‘Victimhood culture,’ Arthur Brookes wrote in the New York Times a decade ago, “has now been identified as a widening phenomenon by mainstream sociologists.”

Though relatively new in scholarship, the psychological phenomenon itself has been around for ages. In his masterpiece The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky explores the human proclivity to manufacture grievance by taking offense.

“A man who lies to himself is the first to take offense. It sometimes feels very good to take offense, doesn’t it? And surely he knows that no one has offended him, and that he himself has invented the offense and told lies just for the beauty of it, that he has exaggerated for the sake of effect, that he has picked on a word and made a mountain out of a pea — he knows all that, and still he is the first to take offense, he likes feeling offended, it gives him great pleasure, and thus he reaches the point of real hostility.”

These words are uttered by Father Zosima, a wise monk tasked with settling a dispute among the Karamazov family. Fyodor Karamazov, the lecherous patriarch, practical purrs in agreement.

“Precisely, precisely—it feels good to be offended,” he replies. “You put it so well, I’ve never heard it before.”

Dostoevsky was observing a psychological tendency: our ability to see ourselves as victims. (Anyone who has watched The Sopranos has seen this idea explored in brilliant artistic fashion.)

Combine that impulse with postmodern philosophies that have turned oppression into a kind of fascination, and you get a potent—and corrosive—worldview.

None of this is to deny that real oppression exists or that people are sometimes treated differently because of their appearance. But the research of Kleck and Strenta suggests that, oftentimes, the perceived discrimination exists only in the minds of those who believe they’ve been wronged.