Executive Summary

Argentina has been in the news lately: first, for its string of foreign debt defaults and hyperinflation, now for Javier Milei, the bold libertarian president attempting to turn the country’s economy around. Contemporary Argentina and its economic challenges are the result of centuries of Argentine history. Over the last several centuries, Argentina has gone through cycles of chaos, economic freedom, and central planning – with the expected economic results. The eighth-richest country in the world in 1910, Argentina gradually fell, becoming the IMF’s greatest debtor by the early twenty-first century. Argentina serves as a case study for the relationship between institutional environments and economic growth, as reality matches the theoretical predictions: economic freedom is a necessary condition for economic growth.

Key Points

- Argentina’s contemporary struggles have roots in a century of central planning.

- Argentina has gone from central planning and misery to economic freedom and prosperity, and back.

- Argentina serves as a case study to illustrate the relationship between institutional environments and economic growth.

- Economic freedom is strongly linked to economic prosperity.

Introduction

Javier Milei – the libertarian, chainsaw-wielding, eccentric, self-proclaimed anarcho-capitalist president of Argentina – has been making headlines. The mainstream press, confused by a president who would slash budgets and restore economic freedom, relishes the string of inaccurate adjectives it uses to describe him, from far-right to neoliberal, or even “ultraliberal.” He inherited an economic disaster and promised a rollback of government spending with a wide array of deregulations to reinvigorate the economy. He has already delivered on those. He also promised dollarization, but as of February 2025 has not yet delivered on it.

To understand Milei’s challenge, we need to step back and examine five centuries of Argentine history, particularly of its institutions. In the tradition of the Austrian economics of Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek, the New Institutional Economics of Douglass North, and the more modern operationalization of those theories in the form of the Economic Freedom of the World index, Argentina’s story of splendor and misery is an institutional story.[1]

Section 1 establishes the institutional prism, with a review of the academic literature on the relationship between institutional environments and economic growth. Section 2 summarizes Argentine history (1500-2023), viewed through an institutional lens. Section 3 describes Milei’s challenge. The final section draws conclusions.

Institutions

1.1 Institutions[2]

Economic theory offers a powerful toolkit for understanding human behavior and economic growth. Much of the standard theory, however, (known as “neoclassical theory”) makes important simplifying assumptions and largely sidesteps some big questions. Douglass North, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1993, founded the school of New Institutional Economics to address such problems.

North worried that neoclassical theory was incomplete, because it ignores the importance of transaction costs and property rights for exchange.[3] He feared that “we have paid a big price for the uncritical acceptance of neoclassical theory. Although the systematic application of price theory to economic history was a major contribution, neoclassical theory is concerned with the allocation of resources at a moment of time, a devastatingly limited feature to historians whose central question is to account for change over time”.[4] Neoclassical economic theory is static, whereas “the central puzzle of economic history is to account for the widely divergent paths of historical change” and for economic growth (or stagnation).[5]

North also recognized a need for a better framework to understand intertwined economic, political, and social change.[6] Enter the study of institutions, the “rules of the game” within which economic activity takes place.[7] North explained how institutions determine the transaction costs faced by economic actors. (Transaction costs are the costs necessary for an economic exchange to happen, but not directly related to it. Think of search costs, working with an agent and going through due diligence to sell real estate, hiring a lawyer to review a contract, or paying a bribe to a government official).[8] Institutions also “reduce the uncertainties involved in human interactions” – uncertainties arising from the complexity of the world in which humans operate, but also from the cognitive limitations of economic actors.[9] Institutions, in sum, are “a mixture of informal norms, rules, and enforcement characteristics [that] together [define] the choice set and results in outcomes.”[10] North addressed this methodological gap by examining transaction costs and the importance of constitutional constraints.[11]

1.2 Institutions and Growth: The Theory[12]

F.A. Hayek, another Nobel laureate in economics (1974), also studied institutions.[13] Hayek concluded that “good” institutions provide good knowledge and good incentives (and “bad” institutions do the opposite). In the realm of knowledge, we can think of prices. In a free market, prices provide knowledge to entrepreneurs about consumer wants, but also about the relative scarcity of inputs. This allows for sound economic calculation and profit-maximization. Conversely, price controls or subsidies distort information, leading to market disequilibrium. Likewise, institutions that shield economic actors from responsibility will lead to moral hazard. Think of banks in the lead-up to the 2007 housing crisis; they responded rationally to bad incentives, making subprime loans to pocket the origination fees and avoid punishment from federal regulators, then promptly sold the toxic mortgages to Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.[14]

The theoretical bridge between institutional environments and economic growth comes from William Baumol’s “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive.”[15] Baumol argued that the institutional environment affects the incentives of entrepreneurs, and will affect the kinds and outcomes of entrepreneurship. With the correct institutions, entrepreneurship will be productive (a positive-sum game, conducive to economic growth and innovation, and contributing to efficient allocation of scarce resources among competing wants; think of Jeff Bezos getting rich by making goods easy to purchase with rapid delivery through Amazon). With the wrong institutions, entrepreneurship can be unproductive (a zero-sum game; think of hiring compliance officers or facilitators who create no value, but are necessary for making business happen). Worse yet, entrepreneurship can be destructive (beyond a redistributive wash, there is a net loss to the economy; for example, entrepreneurs might lobby to reduce competition, enriching themselves at the expense of consumers and competitors, but also hurting innovation). Alas, many governments have not heeded the lessons: most countries in the world suffer from either too little government, or too much.[16] Ineffective governments are incapable of providing the basic governance, rule of law and defense of contracts and property rights required for productive entrepreneurship; overbearing governments are actively involved in picking favorites and redistributing resources to them, thus fostering unproductive or destructive entrepreneurship.

In more blunt language, Peter Boettke summarizes the problem by likening the economy to a race among three horses: “one named Smith (for gains from trade)”; the “second one named Schumpeter (for gains from innovation)”; and the “third one named Stupidity (for… government-imposed obstructions).” He concludes with optimism: “as long as the Smith and the Schumpeter horses were running ahead of the Stupid horse, tomorrow will be better than today.” He then invites us to consider an alternative scenario: “what if the Smith and Schumpeter horses were able to run freely, without that Stupid horse biting at their heels and bumping into them rather than staying in his lane?”[17]

1.3 Institutions and Economic Growth: The Practice

A rich academic literature has explored the link between institutional environments and economic growth.[18]

The late Gerald Scully was a pioneer of measurement. He found empirical evidence for the theory: politically open societies grew at 2.5 percent per annum versus 1.4 percent for politically closed societies; countries that followed rule of law grew at 2.8 percent per annum versus 1.2 percent for those that didn’t; and countries that respected property rights and market allocation grew at 2.8 percent per annum versus 1.1 percent for those with central planning and limited property rights. These differences may seem small. But consider, with compound growth, that a mere difference of 2 percent annual growth versus 2.5 percent annual growth amounts to a 20 percent difference over a generation, 75 percent over 50 years, and 400 percent over a century. Considering that countries with political and economic freedom start at an advantage, we see an already vastly larger economy growing vastly faster.[19]

More recently, the late James Gwartney and his collaborators picked up the research agenda on economic freedom, with the Economic Freedom of the World Index.[20] The index measures the level of economic freedom for each country, using a five-point measurement.[21]

Area 1: Size of Government

Almost all government spending is financed through either current taxation, future taxation (debt), or inflation. When a government spends money, therefore, it necessarily expropriates resources from its citizens, limiting their economic choices. Countries with lower levels of government spending, lower marginal tax rates, less government investment, and less state ownership of assets earn higher ratings in this area of economic freedom.

Area 2: Legal System and Property Rights

When a person and his rightfully-acquired property is not secure, others (both private individuals and the state) may limit his economic choices. Jurisdictions that operate under the rule of law, that ensure the security of property rights, that have independent and unbiased judicial systems, and that impartially and effectively enforce the law, earn higher ratings in this area of economic freedom.

Area 3: Sound Money

Money is involved in nearly every transaction in an economy. If a government’s monetary authority creates significant and unexpected inflation, it makes money less valuable and expropriates property from savers. Conversely, if the government creates significant and unexpected deflation, it makes money more valuable and expropriates property from borrowers. Thus, high and volatile inflation and deflation interfere with individuals’ economic choices. Those jurisdictions that permit their citizens access to sound money — i.e., currencies that maintain their value over time — earn higher ratings in this area of economic freedom.

Area 4: Freedom to Trade Internationally

When a government imposes taxes or regulations at the border, it limits its citizens’ ability to engage in voluntary exchange with people from other countries. Those jurisdictions with low tariffs, easy and efficient customs clearance, a freely convertible currency, and few controls on the movement of physical capital and labor earn higher ratings in this area of economic freedom.

Area 5: Regulation

When government regulations restrict entry into a market, limit or dictate the terms of certain types of exchange, or otherwise dictate how people and businesses may engage in economic activity, they limit individuals’ economic choices. Jurisdictions that impose fewer and less burdensome restrictions on credit markets, labor, business activity, and competition earn higher ratings in this area of economic freedom.

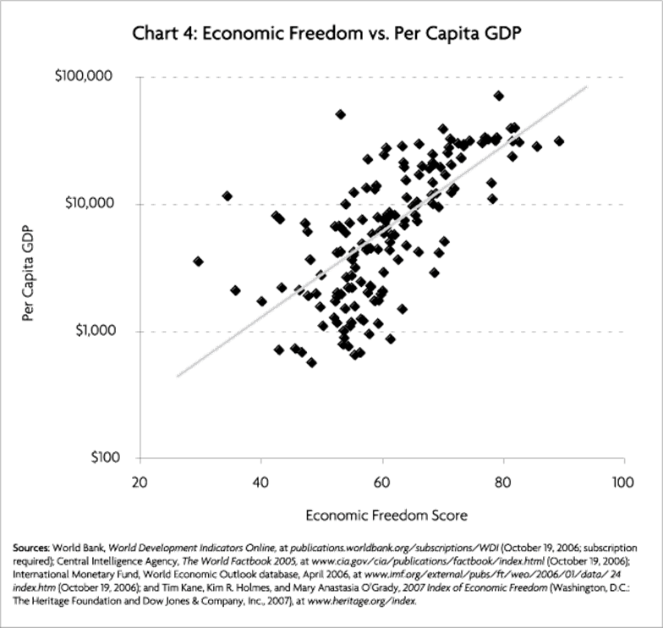

Not surprisingly, the Economic Freedom of the World index finds a clear correlation between economic freedom and economic growth.

Similarly, The Economist recently reported on the stalled decline in international poverty, after 30 years of progress from globalization.[22]

This regress is no coincidence. Freedom House reports that we are in the eighteenth year of democratic decline around the world.[23] This has two consequences. First, as explained above, politically open societies grow faster than politically closed societies. Second, drops in political freedom are often associated with drops in economic freedom. Indeed, in parallel to the world’s drop in political freedom, a decade of growth in economic freedom was erased in 2020, as governments around the world addressed the pandemic with spending and regulation (which were supposed to be emergency measures).[24] Although the world’s politicians are increasingly enamored of central planning, a basic understanding of institutions leaves us completely unsurprised that the recent decline in economic and political freedom would lead to a decline in alleviation of world poverty.

1.4 Conclusion: Institutions Matter

Economic activity does not exist in a vacuum. Growth, capital accumulation, and innovation don’t just happen. Entrepreneurs must have the right incentives and knowledge to find better ways to serve the consumer and drive the economy. The space within which they operate is the institutional framework. In its (successful) quest to develop powerful tools to explain and predict human behavior, mainstream economics has simplified away the institutional foundations of economic activity. Without jettisoning the powerful insights of economic analysis, we can add a rich layer of explanatory power by returning to a study of the underlying institutional environment.

I close this section with a note of caution. Governments can indeed play a “negative” role when it comes to institutions: they can provide rule of law, property rights, defense of contracts, and economic freedom – then get out of the way. But it will be tempting for governments to play a “positive” role. They might do this by picking favorite industries or enterprises and financing them with taxpayer money. Or they might do so by engaging in comprehensive attempts to redesign society and its institutions. Such attempts, because of problems of knowledge (as described by the Austrian school) and incentives (as described by Public Choice theory) usually end with negative unintended consequences. To wit, as we will see below, Argentina’s founders blithely assumed that they could import the US constitution and graft it onto the Argentine tree, without considering culture and other factors; the gamble worked – magnificently – for a while, but the constitution failed to constrain the growth of the state.[25]

A Brief History of Argentina (Through an Institutional Lens)[26]

This section will briefly review 500 years of Argentina history, through an institutional prism. As we will see, in lockstep with institutional change, Argentina went from poor (before its constitution of 1853) to rich (thanks to the economic growth fostered by that constitution) to poor again (because of the Peronist, interventionist betrayal of the constitutional order).

2.1 Prelude: 1500-1853

Argentina was the poor backwater of the Spanish colonial empire. It had no gold, and no widespread indigenous population to exploit as labor. The fertile soil, the port of Buenos Aires, and smuggling were the region’s only major resources. It was not until 1776 that the Spanish crown created a separate viceroyalty of La Plata, with its seat in Buenos Aires. Importantly, the province of Buenos Aires was not just prominent, economically and politically; it was essentially the only game in town. Other cities existed, and there were regional caudillos (strongmen). But none could compete with Buenos Aires. Imagine the thirteen colonies (of the future US) in 1776. Now, instead of thirteen roughly balanced colonies, imagine an overwhelmingly powerful New York. Instead of merely holding the greatest economic power, New York City (capital of a powerful New York State) would be the only significant port on the Eastern seaboard, controlling the customs loot from all transatlantic trade. It would also be the only major city in the thirteen colonies. This sets the stage for understanding the century-long conflict between the province of Buenos Aires and the other provinces. We must also recall that Washington, D.C. was a post-constitutional creation, whereas Buenos Aires (the province, and not just the city) was already a power seat.[27]

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Argentina was still a poor backwater, with a mere 400,000 inhabitants for an area of just over one million square miles.[28] In 1808, the Spanish throne fell to the Napoleonic wars, as Napoleon replaced the King of Spain with his brother Joseph. Uncertainty followed in the Spanish colonies, which were divided between continued loyalty to the deposed King of Spain, allegiance to the new crown, and independence. Buenos Aires proclaimed a half-hearted independence, pledging loyalty to the deposed king, for itself and in the name of the other provinces of La Plata (but without consulting them).[29] The Proclamation of 1810 was neither revolutionary nor independentist, but merely a stopgap measure to fill a power vacuum.[30] After six years of civil war between loyalists and secessionists, the provinces formally proclaimed their independence in 1816.

The next half-century was marked by instability and bloodshed, in a cycle between anarchy and leviathan.[31] This instability came from a lack of vision, structure, or guiding principle in the 1810 Proclamation; some wanted a constitutional monarchy, others a republic. The status of Buenos Aires and its relationship with the other provinces was up in the air. The 1816 Proclamation also lacked a political vision.[32]

1810 to 1829 was a period of anarchy, as described in its horrible detail by fiction author and future president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.[33] Regional caudillos fought each other in their quest for power; Buenos Aires continued its attempts to control the other provinces. Out of this chaos emerged a stronger caudillo, Juan Manuel Rosas, who gained control of Buenos Aires, through which he ruled over all the provinces from 1829 to 1852. The Rosas dictatorship began “not by force or coup, but by the consent of the legislature and the acquiescence of a society exhausted by war and anarchy.”[34]

Rosas enjoyed massive popular support. Because he quashed the criminal power struggles and tamed the local caudillos, Rosas was known as El Restorador de las Leyes (the restorer of the laws). As a dictator, though, he was more concerned with imposing his will and supporting his cronies than about restoring economic freedom or rule of law. Rosas gave Argentina a respite from the chaos, but not a constitutional order.[35]

As institutional economics teaches us, neither anarchy nor leviathan is propitious for economic development. Argentina lacked stability, rule of law, predictability, or defense of basic rights. Consequently, it remained poor during the first half of the nineteenth Century.

2.2 The Constitution of 1853

Argentina’s founding father and constitutional drafter, Juan Bautista Alberdi, examined Argentina’s problems and proposed solutions in his 1852 Bases y Puntos de Partida para la Organización Política de la República Argentina (foundations and points of departure for the political organization of the Argentine republic).[36] As he saw it, the problem was rather simple: tyranny and lack of economic development. He proposed a strong presidency and US-inspired checks and balances to prevent tyranny, thus fostering economic growth.

Alberdi believed many of Argentina’s difficulties could be traced to constitutional choice.[37] He argued there were two constitutional phases in Latin America.[38] The first, immediately following independence, was backward-looking and sought to clean up the shortcomings of earlier systems, rather than addressing fundamental problems. Furthermore, the earlier driving goal was independence from the Spanish crown, not economic development.[39] In the second phase of constitutionalism, there was no longer a need for independence, but for economic development through better institutions.[40]

Economic growth was to take place based on three factors. First, immigration to populate the country, and provide a labor force.[41] Second, sound and stable institutions, to attract foreign capital investment.[42] Third, an active state role in developing the economy – not only by providing a favorable institutional environment, but also by actively guiding and encouraging investment.[43]

Such was Alberdi’s admiration for his northern neighbors that the Argentine Constitution of 1853 was an almost-verbatim translation of the US constitution of 1787 – with a few exceptions. The Argentine constitution of 1853 established a federal system under an entrenched constitution, with united provinces and a federal government (to balance protection of local interests with the fear of local tyranny). The federal government enjoyed enumerated powers, divided among three branches, like the US. The first and most important difference lies in the role of the presidency: fearful of the post-independence cycle of anarchy and tyranny, Alberdi explained that “strong public power is indispensable in Latin America.”[44] He thus proposed a powerful executive, one who could “assume the powers of a king the instant that anarchy disobeys him as republican president.”[45] He concluded that it would be better to give despotism to the law than to a man, because the constitution would check presidential tyranny.[46] This presidential strength is most visible in the power of “intervention,” i.e. a federal overruling of provincial laws and elections. Unlike the US, the Argentine constitution explicitly granted the federal government an activist economic role.[47]

Splendor: 1853-1930

Dissent began to grow against the Rosas dictatorship. By the early 1850s, there emerged a competing caudillo, José Justo Urquiza, who challenged Rosas’s power. The other provinces, keen on overthrowing the hegemony of Buenos Aires, rallied behind Urquiza, who defeated Buenos Aires’s forces in 1852. As part of the peace treaty, Buenos Aires agreed to join the other provinces in a confederation under Alberdi’s proposed constitution.

But Buenos Aires almost immediately backed out of the agreement. The province seceded from the confederation, refusing to submit itself to the other provinces or regional caudillos. There followed an awkward period with two de facto countries (the United Provinces and the Province of Buenos Aires). In 1859, Buenos Aires attempted to invade the other provinces, but was defeated. A compromise was reached, in which Buenos Aires proposed amendments to weaken the constitution’s federalist elements, and thus protect its own interests. In 1860, Buenos Aires ratified the amended constitution, and the country was reunited.[48]

In the ensuing half century, Argentina grew into the eighth richest country in the world (in total wealth), thanks to stability and institutions that promoted economic activity.[49]

Alas, from 1860 into the early twentieth century, Argentina also suffered from deep pathologies under the veneer of constitutional success. Power transfers were peaceful, but relied on fraudulent elections and a self-perpetuating oligarchy; suffrage was not universal, and the president was said to be selected at the elite Jockey Club, rather than through open democracy. Regional caudillos were checked by the national government – at the price of a strong presidency and weak institutional counterweights. The opposition, boosted by the universal suffrage law of 1912, finally broke the oligarchy’s hold on power in 1916. There followed fourteen years of populist rule, a period distinguished by wealth redistribution and social laws that violated the letter and spirit of the Argentine constitution. The constitutional order behind the economic miracle had begun to erode.

2.3 Misery: 1930-2023

Within just a few years, Argentina’s power dynamic had changed suddenly. Presidents had been picked privately by the elites in the proverbial smoky back rooms; that practice was changed with universal suffrage. Adding insult to injury, the post-1860 constitutional order of economic freedom was replaced by increasing interventionism and redistribution. The patience of the economic and political elites grew thin. In 1930, they backed a military coup that ousted the president. This was to be the first of 11 military coups (and six military dictatorships) in the twentieth century. Argentina never recovered from the twin onslaught of populism and militarism.

In 1930, the generals left quickly, after having re-established the conservative oligarchy. In 1943, the military returned, this time as part of a populist swing. A relatively junior officer, Colonel Juan Domingo Peron, participated in the coup, and was rewarded with a ministerial portfolio. As minister of labor, he created an Argentine version of Mussolini’s fascism, combining populism, clientelism, redistribution of public funds to buy votes, and corporatism among the country’s various economic and political power groups, with a balance brokered by a powerful state. In 1946, he was elected president, then re-elected in 1952.

The economy suffered terribly from Peronist redistribution and populist control of the economy. By 1951, Peron had to dampen his policies in order to revive a stagnant economy. Labor, unhappy about losing its privileges, rebelled and supported an attempted coup. In 1955, Peron resigned to avert open civil war. The military stepped in to replace him. (After two decades in exile, Peron returned to Argentina and its presidency in 1973. He died a year later, but still casts a shadow on Argentine politics.)

After 1955, Argentina suffered from a waltz of unstable civilian regimes and military coups. After a counter-coup in 1956, the military allowed elections to take place in 1958, but the new government was thwarted by labor interests when it tried to cut public spending. In 1962, the military canceled the election, overthrew the government, then allowed elections to take place in 1963. The military returned in 1966, this time implementing bureaucratic-authoritarianism. Labor unrest and subsequent violent crackdowns in 1969 heralded the beginning of Argentina’s infamous “dirty war,” with full suspension of due process and constitutionally protected rights. In 1971, a military coup ousted the sitting military government. The 1973-1976 civilian government was weak. Peron died within a year of regaining office, and was replaced by his second wife. The government was soon overwhelmed by the rise of domestic terrorism. Again, economic reform was thwarted by strikes. The dirty war continued, and the economy suffered. In 1976, the military returned to power, and escalated the dirty war to unprecedented heights. Between 1976 and 1983, an estimated 30,000 Argentines were “disappeared” by the military dictatorship.

Five-year economic plans, heavy labor and economic regulations, and a redistributive state all contributed to Argentina’s steady decline. Through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Argentina’s economy was slowly suffocated by Peronism.

The military defeat against the UK in the Falkland/Malvinas Islands, combined with hyperinflation, depression, and debt default, all eroded the military’s support. In 1983, the country returned to civilian rule. The army rebelled four times between 1987 and 1990, albeit unsuccessfully. Whereas the coups that occurred between 1930 and 1976 enjoyed overwhelming popular support, the post-1983 rebellions encountered a different response. Tens of thousands of civilians descended into the streets, and refused to leave until the military returned to their barracks.

Though Argentina returned to civilian rule in 1983, Peronism and interventionism continued, and the country– once the eighth richest in the world – has suffered from stagnation and hyperinflation throughout the decade.

The situation improved in the 1990s, as structural adjustments and privatizations attracted foreign investment. Argentina seemed to have recovered from its political and economic woes, and was hailed as an IMF poster child. Then foreign debt and domestic spending spun out of hand, and Argentina defaulted on its obligations in 2001 (it would default again in 2014 and 2020). In 2001, Argentina endured a sharp economic crisis; in the face of civil unrest and economic disaster, it suffered a string of five presidents in less than two weeks.

Argentina returned to stability for a decade. Then, from 2013 to 2023, Argentina saw a renaissance of Peronism. Institutional counterweights were destroyed, as the Supreme Court was packed with presidential allies; a nominally independent central bank became a financing instrument for massive redistribution; statistics were cooked so profoundly that The Economist simply stopped reporting them for several years. Deficits soared, and hyperinflation, which had been beaten in the 1980s, returned, with rates pushing 300 percent. Poverty grew from 10 percent to 45 percent of the population.

The following graph shows Argentina’s steady decline, as it fell from 80 percent of US GDP in its 1910 heyday to about 30 percent when Milei was inaugurated in December 2023.[50]

Milei’s Challenge: Hope for Argentina?

Javier Milei was elected on a classical liberal platform of reform, and inaugurated in December 2023. He faced deep macroeconomic, structural, monetary, and regulatory challenges – along with deeply entrenched political interests and state clients – all of which have asphyxiated the economy over the past decade and impeded Argentina’s prosperity.

Milei immediately promised he would cut public spending, while raising a few taxes (on imports and exports, notably) to attack the ballooning budget deficit. His most ambitious policy has been implemented through an emergency decree (as authorized by the constitutional amendments of 1984, in case of emergency, the president can impose certain measures, without prior authorization by the legislature). The emergency decree of December 2023 contains 366 articles aimed at saving Argentina’s economy.[51] These articles can be summarized in 30 bullet points. Most of them involve deregulation: of labor markets, healthcare, consumer protection, price controls, impediments to contracts, labor markets, and more. In sum, Milei is engaging in a frontal assault against 80 years of interventionism, populism, and clientelism.

Two things are worth noting. First, Milei inherited an awful dilemma. The recent Peronist acceleration increased national poverty from 10 percent to 45 percent of the population in a single decade. In the long run, the solution is obvious: follow the lessons of institutional economics, roll back corporatism and intervention, and let the economy grow. In the short run, however, the poorest (fully half the population) will suffer even more as they lose palliative public welfare. To remedy this, as the economy suffers before it grows, the Milei administration immediately doubled welfare and food aid to children. Second, Milei is slowly re-establishing rule of law to end the blackmail by the Peronist labor unions. Contrary to four decades of practice, any person blocking entry or egress from factories, or blocking roads during a strike action, will be fired or arrested, and will lose all government benefits. The right to strike, due process, and habeas corpus remain. Argentina was in the bottom quartile of world economic freedom during the latest rankings – but it continues to enjoy high levels of political freedom.[52]

On the monetary side, Milei was quickly caught in a difficult reality. He gave up on the immediate closing of the Argentina central bank, as well as on the dollarization he had promised. Milei likely worried about Argentina’s weak official dollar reserves and feared the consequences of a drastic reduction in the country’s money supply, which would have led to further poverty and the possibility of social unrest. Inflation has decreased, as the Argentine state is no longer printing pesos to cover its lavish spending and budget deficits. Milei has reduced inflation from a high of almost 300 percent p.a. when he took office to about 166 percent at the close of 2024. Work remains, but progress is visible, thanks to both macroeconomic and microeconomic reforms.

Milei did not immediately dollarize, but he did take a step in the same direction by partially suspending legal tender laws, and allowing private contracts to be made in foreign currencies, as well as cryptocurrencies.

Sadly, Argentina, which has already suffered so much under Peronism, is set to suffer even more during the austerity period (Milei, ever the political showman, warned Argentines of a very precise 17 difficult months). We are reminded here of the parallel F.A. Hayek drew between the recovery from the boom-and-bust cycle of monetary expansion, and withdrawals after overconsumption of alcohol. Faced with a hangover, we face a difficult choice: accept the consequences of last night’s joy, or postpone the suffering by reaching for the bottle on the nightstand… then rinsing and repeating tomorrow, with an even worse hangover. Argentina is facing the consequences of a twenty-year binge. It periodically wakes up with a hangover (in the form of a debt crisis or inflation). Instead of reforming its ways, Argentina keeps relying on outside loans or monetary expansion to get itself out of crisis; but this is always a temporary measure, at best. The cycle has continued. Milei is attempting to break that cycle, but there will be more short-term pain during withdrawals.

Beyond macroeconomic stabilization, Milei faces an uphill battle. He was elected with more than 50 percent of votes cast (rather than a mere plurality). But he is facing deeply entrenched interests that are not keen to lose their privileges and their place at the public trough. (As of February 2025, Peronists controlled 31 of 72 Senate seats, 102 of 257 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, and 11 of 24 provincial gubernatorial mansions.) Even though a majority of the people support Milei, he is facing pushback from Peronists, labor unions, public employees, and others who have lived for so long on the proceeds rent-seeking. Milei is victim of a classic Public Choice story, which reaffirms that individuals do not magically turn into public-spirited angels when they are employed by the state or are reminded of the common good.

Public Choice theory explains political coalitions, elite collusion beyond party lines, and much more. The theory of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs developed by economist Mancur Olson applies here.[53] Inefficient and unfair policies will persist if the cost is spread out over much of the population, while the benefits are concentrated on few recipients. Those who bear the cost will likely not be aware of the problem, and the cost of organizing to end the redistribution will be higher than the cost paid. Those who receive the benefit will be politically organized and have resources to secure continued goodies. Politicians love such schemes, as the beneficiaries will support their re-election, and the payers won’t complain effectively.

For example, Americans pay, on average, $10 per year to support an inefficient American sugar industry, with an estimated loss of 20,000 jobs per year in the food industry which uses sugar as an input. But it’s not worth organizing politically to end a $10 annual cost. In sum, though, this translates to $4 billion annually for the sugar industry, which deftly ensures they will lobby for a continued subsidy.

How much time Milei has is unclear. An emergency decree stays effective for one year, unless both chambers oppose it. Since 1994, the political tradition has been for the legislature not to oppose emergency decrees; however, under Peronism, decrees always expanded public spending, with concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. Milei’s cost-slashing is a threat to those who receive concentrated benefits, and to their political allies. The Senate rejected the decree in March 2024, but the lower chamber accepted it. As a result, Milei continues to face the dilemma of working with Peronist legislators and state governors (the latter were irked that the federal government suspended payments to them, as part of the deficit-slashing).

Time will tell if Milei can turn Argentina around in 17 months, as promised. He must tame hyperinflation, continue to cut public spending, and lower poverty, as he jump-starts the economy – or technically, as he removes state fetters from an economy already eager to surge forward.

Dollarization presents an interesting institutional question. Indeed, it is not, technically speaking, economically necessary; following the model of F.A. Hayek, denationalization of currency is an alternative to dollarization or the free emission of money (free banking).[54] This would happen with full abolition of legal tender laws. But ending the central bank is institutionally crucial. Milei’s deregulation and cost-cutting could be overturned by the next legislative majority or presidential decree, but it would be much harder to re-establish in the absence of central banking. Without a central bank to print money, Peronist largesse would be impossible. Ending the central bank is the credible commitment required for Argentina’s long-term growth and recovery.[55]

In the summer of 2024, Milei moved in this direction, declaring an amnesty on dollars held in Argentina and abroad – partly as a show of good faith, and partly to measure the quantity of dollars already in the country. Dollarization is thus on the path to happening de facto. But the central bank must go.

History teaches us that growth and stability flow from institutions – institutions, such as rule of law, respect for property rights and contracts, space to innovate and exchange, stability, trust, and predictability. Milei’s challenge thus remains, fundamentally, a challenge of institutional reform.

Conclusion

Argentina provides a case study for a fundamental lesson in economics. Institutional environments are inextricably linked with economic growth. Policymakers can try all manner of redistribution, international aid, investment, macroeconomic reforms, and bold ideas, but growth will not happen if institutions do not support it. For growth to happen, entrepreneurs must be able to innovate and drive the economy. Entrepreneurs must be allowed to operate within a predictable institutional environment that provides them (or at least does not destroy) with incentives to do so.

Javier Milei has taken to hearing the lessons of institutional economics. By ending the deficit, cutting spending, and decreasing inflation, he has provided the macroeconomic foundations for microeconomic reforms of deregulation and increased freedom of contracts and commerce. In just one year, he has made great strides, but he has had little time to address eight decades of Peronist interventionism. He enjoys the support of an Argentine population that is so fed up with Peronism that it will endure some austerity. Milei still faces an uphill battle against the interest groups that benefit from redistribution and state power.

His initial successes are a source of hope; poverty, under Milei’s austerity program, soared past 50 percent but has already fallen to 37 percent. Inflation has fallen. A static real estate market has already shown the vibrancy of liberation. While the Argentine economy is still sputtering, it has exited recession under Milei. The key will be long-term strengthening of institutions that ensure economic liberty.

Endnotes

[1] This paper draws on and updates Nikolai Wenzel, “Matching Constitutional Culture and Parchment: Post-Colonial Constitutional Adoption in Mexico and Argentina,” Historia Constitucional No. 10 (2010), 321-338.

[2] This section borrows from Andrés Marroquin and Nikolai Wenzel, “Introduction”, in A Companion to Douglass North, ed. Andrés Marroquin and Nikolai Wenzel (Universidad Francisco Marroquin, 2020), 5.

[3] Douglass North, Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance (Cambridge University Press, 1990a), 11.

[4] Ibid, 131.

[5] Douglass North, Understanding the Process of Economic Change (Princeton University Press, 2005), 11. See also North 1990a, 6-7.

[6] North 2005, vii.

[7] North 1990a, 3.

[8] Ibid, 6.

[9] North 1990a, 25 and chapter 3. See also North 2005, 83 on the importance of mental models in limiting human behavior, but also in the process of institutional change).

[10] North 1990a, 53.

[11] North 1990a, 3. John Joseph Wallis and Douglass North, “Measuring the Transaction Sector in the American Economy,” in Long-Term Factors in American Economic Growth, ed. Stanley Engerman and Robert Gallman (University of Chicago Press, 1986), 95-162. North examined the importance of transaction costs in Douglass North, “A Transaction Cost Theory of Politics,” Journal of Theoretical Politics 2, No. 4 (1990b), 355–367.

[12] For the sake of simplicity, I am leaving out informal institutions (such as trust, time preferences and propensity to save, culture, social capital, or ideology) and the mental models that drive decisions. North himself recognized the importance of informal institutions. On informal institutions, see Claudia Williams, “Informal Institutions Rule: Institutional Arrangements and Economic Performance,” Public Choice 139, No. 3/4 (2009), 371-387 or Deirdre McCloskey, The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce (University of Chicago Press, 2006). On mental models, see North 2005, F.A. Hayek, “The Facts of the Social Sciences,” in F.A. Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order (University of Chicago Press, 1948), 57-76, or Nikolai Wenzel, “An Institutional Solution for a Cognitive Problem: Hayek’s Sensory Order as Foundation for Hayek’s Institutional Order” in ed. William Butos, The Social Science of Hayek’s “The Sensory Order” (Emerald, 2010,) 311-335. For a scathing attack on New Institutional Economics, see Deirdre McCloskey, “Austrians Should Reject North and Acemoglu: Some Critical Reflections on Peter Boettke’s The Struggle for a Better World,” Review of Austrian Economics (forthcoming).

[13] See, notably, F. A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (University of Chicago Press, 1960).

[14] See Alexandra Mussler and Nikolai Wenzel, “The Financial Idea Trap: Bad Ideas, Bad Learning, and Bad Policies after the Great Financial Crisis,” Cosmos + Taxis 8, No. 2 (2020) and Steven Horwitz and Peter Boettke, “The House that Uncle Sam Built: The Untold Story of the Great Recession of 2008” (Foundation for Economic Education, 2009)

[15] William Baumol, “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive,” Journal of Political Economy 98, No. 5, Part 1 (1990), 893-921. See also Nikolai Wenzel, “Editorial: Three Intellectual Debts and the Three Horses of Entrepreneurship: The Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy Celebrates Ten Years,” The Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy 12, No. 1 (2023), 1-5.

[16] See James Buchanan, The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan, in The Collected Works of James M. Buchanan, Volume 7 (Liberty Fund, 1975[2000]). See also James Gwartney, Richard Stroup, Russell Sobel, and David MacPherson, Economics: Private and Public Choice, 16th edition (Cengage Learning, 2017).

[17] Peter Boettke, “Imagine a Horse Race Between Smith, Schumpeter, and Stupidity,” The Daily Economy (American Institute for Economic Research, 2020).

[18] See Randall Holcombe, “Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 1, No. 2 (1998), 45-62; Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (Basic Books, 2000), Peter Boettke and Christopher Coyne, “Entrepreneurship and Development: Cause or Consequence?,” Advances in Austrian Economics 6 (2003), 67-88; Christopher Coyne and Peter Leeson, “The plight of Underdeveloped Countries,” Cato Journal 24, No. 3 (2004), 235-249; or Russel Sobel, “Testing Baumol: Institutional Quality and the Productivity of Entrepreneurship,” Journal of Business Venturing 23, No. 6 (2008), 641-655. See also Gwartney et al. (2017).

[19] Gerald Scully, “The Institutional Framework and Economic Development,” Journal of Political Economy 96, No. 3 (1988), 652-662. Gerald Scully, Constitutional Environments and Economic Growth (Princeton University Press, 1992).

[20] www.freetheworld.org

[21] https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/economic-freedom-what-is-it-how-is-it-measured.pdf

[22] https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/09/19/the-worlds-poorest-countries-have-experienced-a-brutal-decade

[23] https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2024/mounting-damage-flawed-elections-and-armed-conflict

[24] https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom

[25] Wenzel (2010). See also Peter Boettke, Christopher Coyne, and Peter Leeson, “Institutional Stickiness and the New Development Economics,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 67, No. 2 (2008), 331-358.

[26] This section draws from Wenzel (2010) and my 2007 doctoral dissertation. For the history, see also Thomas Skidmore and Peter Smith, Modern Latin America, 5th edition (Oxford University Press, 2000).

[27] Arthur Whitaker, The US and the Southern Cone (Argentina, Chile, Uruguay) (Harvard University Press, 1976), 28

[28] Armando Ribas, Argentina, 1810-1880: Un Milagro de la Historia (VerEdit, 2000).

[29] Nicolas Shumway, The Invention of Argentina (University of California Press, 1991), 21.

[30] Ribas 2000, 38.

[31] This borrows from the title of Buchanan (1975).

[32] Ribas 2000, 44, 46.

[33] Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Facundo, O Civilización y Barbarie en las Pampas Argentinas, (Emecé Editores, S.A., 2000[1874]).

[34] Shumway 1991, 118.

[35] Sarmiento 2000[1874], 252-258.

[36]Juan Bautista Alberdi, Bases y Puntos de Partida para la Organización Política de la República Argentina (Academia Nacional de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales de Córdoba, 2002[1852])

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid, 13.

[39] Ibid, 14.

[40] Ibid, 38.

[41] Ibid, 57.

[42] Ibid, 57.

[43] See Juan Bautista Alberdi, “Sistema Económico y Rentístico de la Confederación Argentina, según su Constitución de 1853,” in Obras Escogidas de Juan Bautista Alberdi, Volume 4 (Editorial Luz del Dia, Buen1954 [1855]).

[44]Alberdi 2002[1852], 35.

[45] Ibid, 124-125.

[46] Ibid,129.

[47] This happened in the US also, of course. However, the US constitution does not explicitly grant vast powers of economic development to the federal government. Those came later, with executive overreach and compliant courts. See Robert Levy and William Mellor, The Dirty Dozen: How Twelve Supreme Court Cases Radically Expanded Government and Eroded Freedom (Cato Institute, 2010). See also Nikolai Wenzel, and Allen Mendenhall “Towards a Return to Constitutional Government: an Economic, Post-Romantic Argument for Ending the Bifurcation of Rights,” Journal of Law & Civil Governance at Texas A&M 1, No. 1 (2024), 1-34.

[48] Shumway 1991, 227.

[49] See Ribas 2000 and Jonathan Miller, “The Authority of a Foreign Talisman: A Study of US Constitutional Practice as Authority in Nineteenth Century Argentina and the Argentine Elite’s Leap of Faith”, American University Law Journal 46, No. 5 (1997), 1483-1572. For context, Argentina’s wealth was on par with that of the first industrialized countries, including the US. See https://www.mercatus.org/research/working-papers/rise-and-fall-argentina

[50] These are dollars adjusted for purchasing power. Data is from Maddison, Angus, Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD

[51] Herald, Buenos Aires. “Milei’s Controversial Mega-Decree Officially Takes Effect.” Buenos Aires Herald, 29 Dec. 2023.

[52] See www.freetheworld.org and https://freedomhouse.org/country/argentina

[53] Mancur Olson,The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities (Yale University Press, 1984).

[54] F.A. Hayek, Denationalisation of Money (Institute for Economic Affairs,1976).

[55] Emilio Ocampo and Alfredo Romano, Argentina Dolarizada: Perspectivas para una nueva Economía (Galerna, 2024).. A static real estate market has already shown the vibrancy of liberation. While the Argentine economy is still sputtering, it has exited recession under Milei. The key will be long-term strengthening of institutions that ensure economic liberty.