Introduction

People in financial markets and in the media regularly track Federal Reserve announcements and forecast what the Fed’s interest rate target will be in the future. But when people speak of the Federal Reserve increasing or decreasing the interest rate, to what are they referring? What interest rates does the Fed target? How does the Fed target them? What are the effects of its interest rate targets? This Explainer addresses those questions.

What the Fed Targets

The Federal Reserve targets an interest rate called the federal funds rate (FFR). The FFR represents the interest rate banks charge one another for overnight borrowing of reserves in the federal funds market. Reserves are money. They include cash that banks keep on hand as well as the money banks hold in accounts at the Fed.

Banks lend and borrow reserves in the federal funds market based on their short-term money needs—these include money to meet depositor withdrawals, to pay out loans made to consumers, and to cover regulatory requirements. How many reserves banks lend or borrow depends on how much money they need to meet these liquidity obligations. Banks with extra reserves lend; those with shortfalls borrow. The amount of lending and borrowing of reserves in the federal funds market affects the FFR.

The Fed can influence this market and the FFR by adding newly created reserves or extracting reserves from the banking system. When the Fed creates more reserves, the FFR falls. This is called expansionary monetary policy because it stimulates economic activity. When the Fed reduces the supply of reserves, the FFR tends to rise. This is called contractionary monetary policy because it reduces available credit and dampens economic activity.

For most of its history, until 2008, the Federal Reserve influenced the FFR market by adding reserves to, or subtracting reserves from, the banking system through open market operations. These operations involved the Fed buying bonds with newly created bank reserves, thereby lowering the FFR, or selling bonds and extinguishing bank reserves, thereby increasing the FFR. Since reserves were relatively scarce in the pre-crisis system, even small interventions by the Fed had predictable effects on the FFR.

In modern times, rather than using open market operations, the Fed relies on three interest rates that it directly sets, or administers, to increase or decrease reserves in the banking system. Through these rates, the Fed influences banks’ borrowing and lending activity in the FFR market. The result is an FFR within the Fed’s interest rate target.

How the Fed Targets the FFR

The three rates the Fed sets to reach its FFR target range are: the discount rate, interest on reserve balances (IORB), and overnight reverse repurchase agreements (ON RRP). The most important are IORB and ON RRP.

IORB is the primary tool the Fed uses to achieve its FFR target. It is the rate the Fed pays banks for reserves kept on deposit at the Fed. For contractionary monetary policy, the Fed sets this rate above what banks can typically earn elsewhere, encouraging them to keep excess reserves at the Fed rather than lending them, thereby exerting upward pressure on the FFR. For expansionary monetary policy, the Fed sets this rate below what banks can earn elsewhere, encouraging them to put more reserves to use in the economy, thereby reducing the FFR.

The ON RRP is the lower bound of the Fed’s FFR target range. It is used to reinforce the Fed’s IORB rate by offering a similar, but lower, interest rate to non-bank financial institutions such as hedge funds, money market mutual funds, insurance companies, and government-sponsored enterprises. These institutions cannot earn IORB because they cannot keep reserves at the Fed. However, they can influence overnight lending markets with their own reserves. Therefore, the Fed offers ON RRP to non-banks to ensure these institutions keep in line with the Fed’s FFR target.

The discount rate is set above IORB and marks the high end of the Fed’s FFR target range. It is the rate that the Fed charges banks for borrowing directly from the Fed at the discount window. Since no bank would pay more than this rate to get reserves, it creates a ceiling on the Fed’s FFR target. Historically, borrowing directly from the Fed carried significant stigma – people in the market interpreted it to mean the bank was high-risk, distressed, or both. Since becoming part of the Fed’s interest rate setting system, however, the discount window stigma has declined considerably.

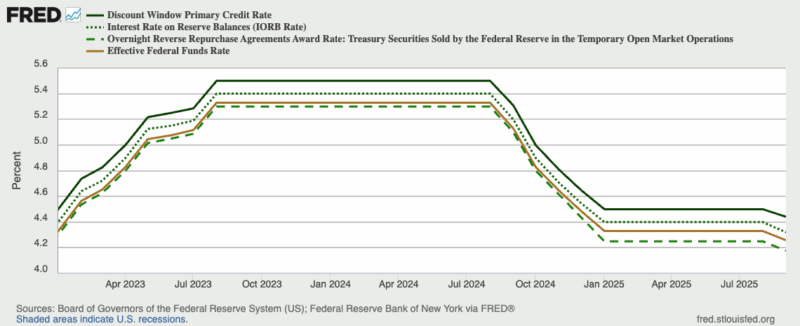

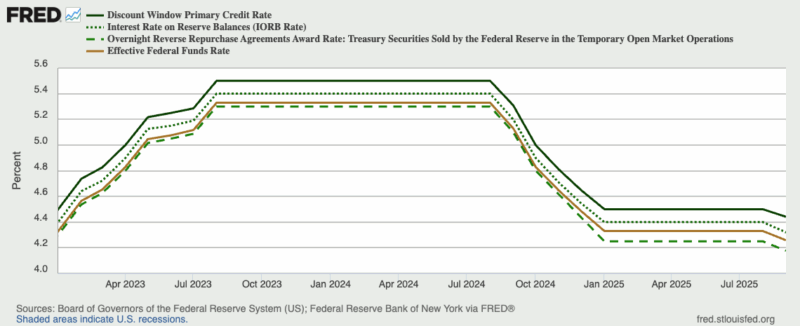

Through August 2025, the Fed’s target FFR range was 4.25–4.5 percent. To achieve its target, the Fed set IORB at 4.4 percent, ON RRP at 4.25 percent, and the discount rate at 4.5 percent. As a result, the effective FFR has landed roughly in the middle of IORB and the ON RRP at 4.33 percent throughout 2025 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Fed Interest Rate Targets Since 2023

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1M3ey

How Interest Rate Targets Interact with the Fed’s Balance Sheet and Banks

While adjusting IORB and ON RRP allows the Fed to manage the FFR in what appears to be a precise fashion, it requires the banking system to have ample reserves. An ample reserve environment means banks have more than enough reserves to meet their short-term money needs with plenty left over to be sensitive to the Fed raising or lowering the IORB. To set rates in this fashion, the Fed has had to dramatically increase both the amount of reserves in the banking system and the size of its balance sheet.

For example, total reserves held by banks historically averaged $50 billion or less. As the Fed started paying interest on reserves in 2008, that number jumped to nearly $1 trillion. It reached a peak of almost $4.2 trillion during the COVID-19 pandemic. By mid-2025, it had declined but remained elevated at more than $3.3 trillion.

Maintaining an ample reserve environment also requires the Fed to maintain a balance sheet significantly larger than under the previous interest rate setting regime. To generate sufficient reserves, the Fed purchases bonds from financial institutions, which increases the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. Historically, the Fed’s balance sheet stood at less than $900 billion. It ballooned to more than $2 trillion during the global financial crisis, only to be dwarfed by a fourfold increase to nearly $9 trillion during the pandemic. In mid-2025, the Fed’s balance sheet stood at roughly $6.6 trillion.

Such large amounts of money hanging on the sidelines of the banking system can quickly lead to inflationary pressures once banks choose to lend those reserves instead of keeping them at the Fed. Combined with the Fed’s large balance sheet, the current system raises concerns about whether the central bank’s interest rate policies lead to either financial repression or credit allocation—areas typically deemed inappropriate for monetary authorities to engage.

How the Federal Funds Rate Affects the Economy

Although the Fed primarily targets and influences the overnight rate of interest, its actions affect other interest rates because they are either indexed to, or built upon, the overnight rate. Additionally, investors shift their holdings of debt and their interest rate expectations based on what the Fed does and signals it will do with the FFR.

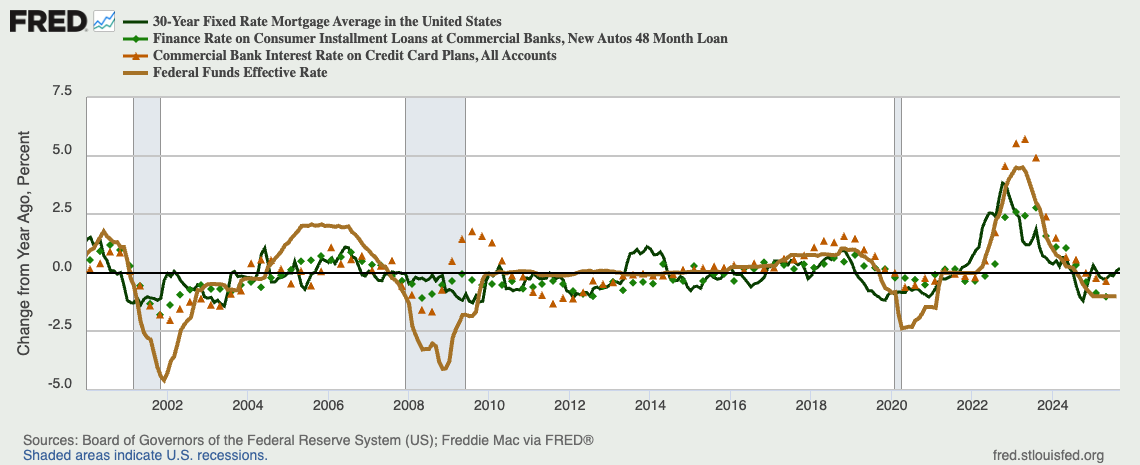

Three important consumer interest rates broadly affected by Federal Reserve interest rate policy are the thirty-year mortgage rate, credit card interest rates, and the interest rate on vehicle loans (Figure 2). Commercial and corporate borrowing are also affected by changes in the FFR target.

Figure 2: Fed Funds, 30-Year Mortgage, 4-Year Auto, & Credit Card Rates Since 2000

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1M3eq

Interest rate changes have many effects on the economy. They change the relative cost for purchases that involve substantial amounts of debt, such as cars and houses. For example, even if there is no change in the sticker price of a $20,000 car, the car can become much more expensive if the buyer uses financing.

If the buyer finances the $20,000 at 5 percent amortized over five years, he will have a monthly payment of $377. But if he finances the $20,000 at 8 percent, his monthly payment will be $406 – a 7.4 percent increase. Although $29 a month may not seem like much, it adds more than $1,700 to the total cost over five years. If you add a zero—a $200,000 mortgage versus a $20,000 car loan—the increased financing cost becomes $290 per month or $3,480 per year. With a 30-year mortgage, that amounts to an increase of more than $100,000.

Interest rates affect the cost of purchasing homes and cars, credit cards, and business loans. Beyond that, they serve as important signals and prices for businesses and investors, acting as a key input for determining the costs and potential returns of entrepreneurial ventures. A slight change can make all the difference between a worthwhile endeavor and a failed one. With many interest rates influenced by the FFR, small changes to the Fed’s FFR target can impact large segments of the economy.

Conclusion

People watch the Fed closely because its decision to change its FFR target affects financial markets and the economy in many ways. Overall, the Fed’s current interest rate setting system has given the appearance of precise control, using IORB and ON RRP to manage the amount of money in the economy. But it has not been without costs. Banks and financial institutions are more dependent on the Fed and its decisions when it comes to how much lending and borrowing takes place in the economy. The current system also requires a large Fed balance sheet and higher levels of reserves. The result is a much larger Fed footprint in the economy that can dampen the efficient allocation of credit as determined by markets and poses risks to price stability—as evidenced by inflation hitting a 40-year high post-pandemic in 2022.