In his novel Ignorance, the late Milan Kundera called nostalgia “the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return.”

Nostalgia is a powerful force, particularly so today.

For years, Hollywood has tapped into our desire to return to the past to cash in. Though Disney’s 2025 flop Snow White shows the formula is far from foolproof, reboots, sequels, and “requels” have dominated at the box office the last two decades: Batman Begins (2005), Transformers (2007), Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Star Trek (2009), Jurassic World (2015), It: Chapter One (2017), Halloween (2018).

I could go on, and this list doesn’t even include Disney’s live-action remakes of hits like Aladdin and The Lion King. It’s not just movies, though.

Take a look around and you’ll see that 1980s and ’90s fashion cycles are back—driven by Gen Z and Millennial interest in “vintage cool” mom jeans, crop tops, and bucket hats. Even mullets are in again, as are retro sneakers and brands like Abercrombie & Fitch. And while Taylor Swift’s “Eras Tour” set a record with its $2.2 billion ticket sales over two years, most of the top-selling tours in recent years were dominated by legacy acts like Metallica, The Rolling Stones, and Elton John, whose “Farewell Yellow Brick Road” tour in 2023 banked a not-too-shabby $939 million in gross sales.

Unsurprisingly, nostalgia has also infiltrated our politics and economic policies. The renaissance of American protectionism has confused many, but it’s a phenomenon some saw coming.

A decade ago, the late economist Steve Horwitz quipped that left-wing politicians had been bewitched by “nostalgia for the economy of the 1950s.” But he added that a Republican upstart appeared intent on stealing from the Democrats’ populist playbook.

“It is more than a little ironic,” Horwitz wrote, “that modern progressives are nostalgic for the very economy that GOP front-runner Donald Trump would appear to want to create.”

Horwitz wrote these words in the summer of 2015 when Trump’s candidacy was still considered a joke by the experts. (A panel of 538 experts pegged his odds of winning the GOP nomination at “2 percent, 0 percent and minus-10 percent, respectively.”) But he secured the GOP nomination in 2016 by breaking from the party’s traditional platform — most notably by opposing immigration and free trade.

Trump’s rise was puzzling. America’s open economy had created new jobs, lifted millions into higher-paying work, and delivered cheaper goods and services to households across the country. Yet Trump’s populist message, centered on economic nationalism, won him both the nomination and the presidency — largely by tapping into a widespread longing to return to a supposed manufacturing Golden Age.

Trump framed his trade agenda as a matter of economic fairness. If other countries use tariffs and trade barriers to boost their industries, why shouldn’t America? But the underlying goal was more ambitious.

“Jobs and factories will come roaring back into our country,” Trump promised on “Liberation Day,” as he announced tariffs that shocked global markets. “We will supercharge our domestic industrial base.”

It’s a vision that appeals to Americans, who have visions of their grandfathers toting lunch buckets to smokestack-studded plants of the 1940s and ‘50s — a supposedly simpler time when work was steady, dignity came with a paycheck, and the factory floor looked and felt like home.

The appeal of “nostalgianomics” is not new.

In his 2009 paper “Paul Krugman’s Nostalgianomics,” Cato scholar Brink Lindsey critiqued Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman’s romanticized view of mid-twentieth-century America. “Krugman looks back to the America of his boyhood and sees a society that combined energetic, activist government management of economic affairs with vigorous growth and converging incomes,” Lindsey wrote. “Entranced by that vista, he imagines a Golden Age — not just of economic performance, but of economic policies and social norms as well.”

Lindsey called this view a case of “ideologically motivated nostalgia,” accusing Krugman and other progressive leaders of cherry-picking history to paint the postwar era as a model of enlightened policymaking and social harmony. Whether through stronger labor unions (Krugman), trade protectionism (Nancy Pelosi), or expanded labor regulation (Hillary Clinton), the common thread was a belief that shielding Americans from the free market could restore that imagined past.

Trump’s own protectionist formula is slightly different; it combines a hostility toward immigration with his disdain of trade and love of tariffs. Regardless, the formula has worked with voters who have long been skeptical about the benefits of free trade and immigration.

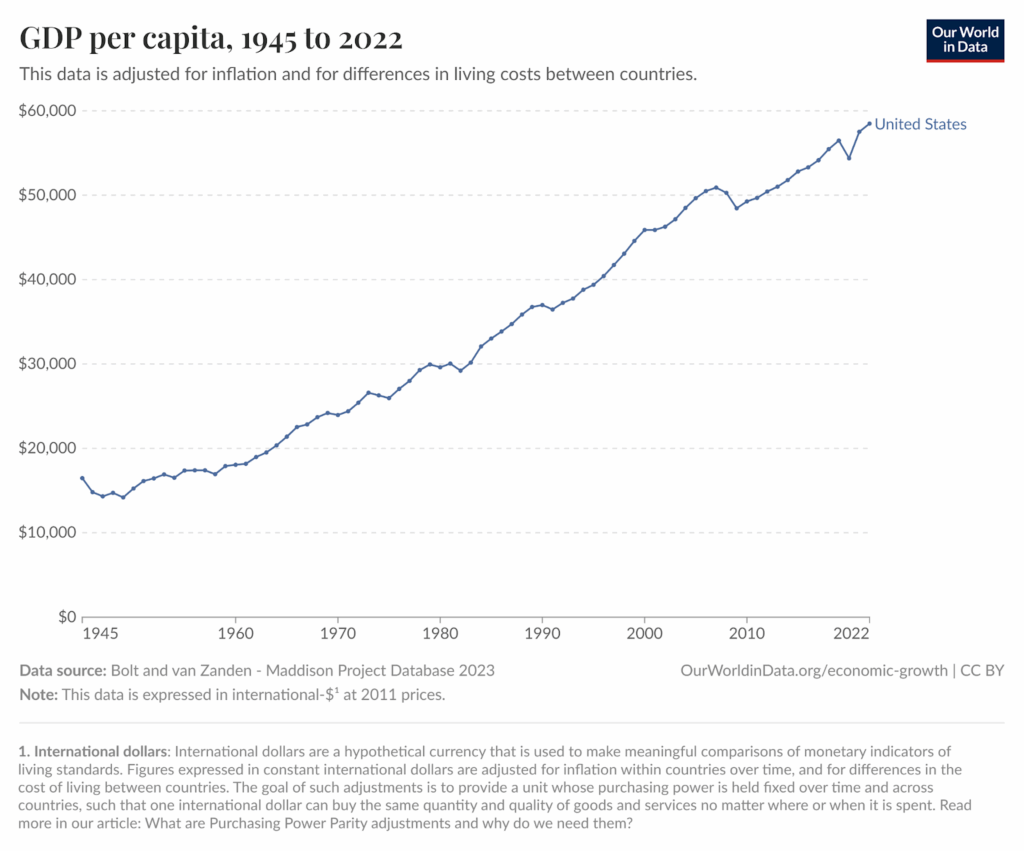

Americans were lukewarm on NAFTA when it was ratified in 1993 and remained so during Trump’s first term. Many still long for the economy of the 1950s — even though wealth per person has quadrupled since the Truman days, in large part because of global trade.

It would be a mistake to blame the resurgence of protectionism purely on nostalgia. Other forces are at work, too.

Yet nostalgianomics plays a large role, and its growing influence would seem to stem from a sense that there is something deeply wrong in America, something politicians must fix.

To be fair, there is indeed a great many things wrong in America today: public education in many cities is failing by every measurable standard; drug overdose deaths have reached historic highs; marriage and birth rates are declining; and rising numbers of young people are detached from both work and community. Throw in a growing (and deserved) distrust in institutions — from government and media to higher education — and it’s understandable that Americans feel agitated and untethered.

These problems, however, do not stem from global trade, which has benefited both Americans and their trading partners.

To continue prospering, Americans must confront some uncomfortable truths — starting with the notion that assembling widgets on a factory line isn’t inherently more meaningful than making lattes in a café, writing code, or designing marketing campaigns.

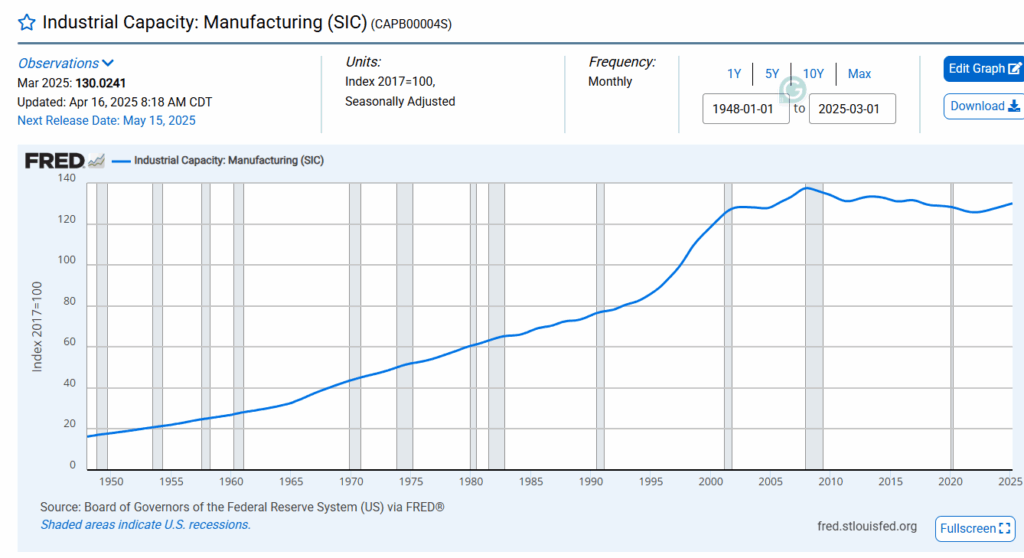

They must also recognize certain truths about manufacturing. Despite the narrative US manufacturing has been “hollowed out” by trade agreements, capacity has increased more than 50 percent since NAFTA was signed and remains at near-historic highs.

While it’s true that manufacturing jobs as a percentage of nonfarm employment have declined substantially, the rate of the decline has slowed significantly since China became a member of the World Trade Organization in 2001. Moreover, the decline in manufacturing jobs has far less to do with trade than with technological advancements that have automated production and increased output with fewer workers — much as they did with farming, which once employed a third of the workforce but now requires less than 2 percent to feed the nation.

Whether Americans are willing to accept these realities is unclear. A recent Cato poll found that 80 percent of Americans say the country “would be better off if more people worked in manufacturing.” Yet the same poll found that just 25 percent of Americans say they themselves would be better off working in a factory job.

The poll reveals a telling disconnect between the romanticized idea of manufacturing and its present-day realities, beginning with the fact that industrial jobs don’t pay nearly as well as people think. This demonstrates a serious challenge to policymakers.

Economists have struggled to counter nostalgianomics precisely because its appeal is rooted more in psychology than economics. It offers a comforting narrative: that America once had an economic system that worked for everyone — and with the right top-down policies, it can again.

In a world increasingly steeped in nihilism and searching for greater meaning and purpose, that’s a message that resonates with a lot of people — even if it’s false.